-

Drones

-

Top pick HS900 48MP | 4K@30fps | 3-Axis | Fast Charge HS790 3-Axis | 6K | 9 km HS600D 3-Axis | 48MP | 4K@30fps HS600 2-Axis + EIS | 3 km | 4K SonyView all →

Top pick HS900 48MP | 4K@30fps | 3-Axis | Fast Charge HS790 3-Axis | 6K | 9 km HS600D 3-Axis | 48MP | 4K@30fps HS600 2-Axis + EIS | 3 km | 4K SonyView all → Top pick HS440 Camera drone without GPS for backyard time HS360S GPS, 3KM Range, 4K camera drone HS360D 4K | 6 km | 80 min Flight HS360E 4K EIS | 6 km | HS280D Skill-Trainer Drone • 1080P 2 Batteries • Brushless Motors HS175G 4K@30fps | EIS | 60 min HS175D Pilot-friendly, GPS, 4K, Brushless MotorsView all →

Top pick HS440 Camera drone without GPS for backyard time HS360S GPS, 3KM Range, 4K camera drone HS360D 4K | 6 km | 80 min Flight HS360E 4K EIS | 6 km | HS280D Skill-Trainer Drone • 1080P 2 Batteries • Brushless Motors HS175G 4K@30fps | EIS | 60 min HS175D Pilot-friendly, GPS, 4K, Brushless MotorsView all →

-

- Accessories

- Blog

-

Support

-

Product SupportSpecs/Downloads/Tutorial Videos/FAQ

- HS900 Support

- HS790 Support

- HS720R Support

- HS720G Support

- HS720E Support

- HS720-4K Support

- HS710 Support

- HS700E Support

- HS600D Support

- HS600 Support

- HS110G Support

- HS460 Support

- HS440G Support

- HS440D Support

- HS440 Support

- HS430 Support

- HS420 Support

- HS360E Support

- HS360S Support

- HS290 Support

- HS280D Support

- HS190 Support

- HS175G Support

- HS175D Support

- View all →

-

- About

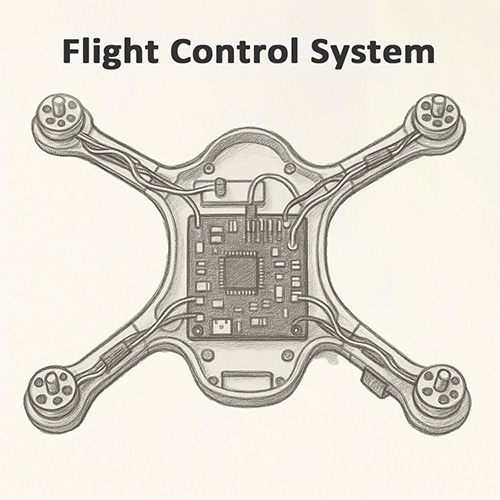

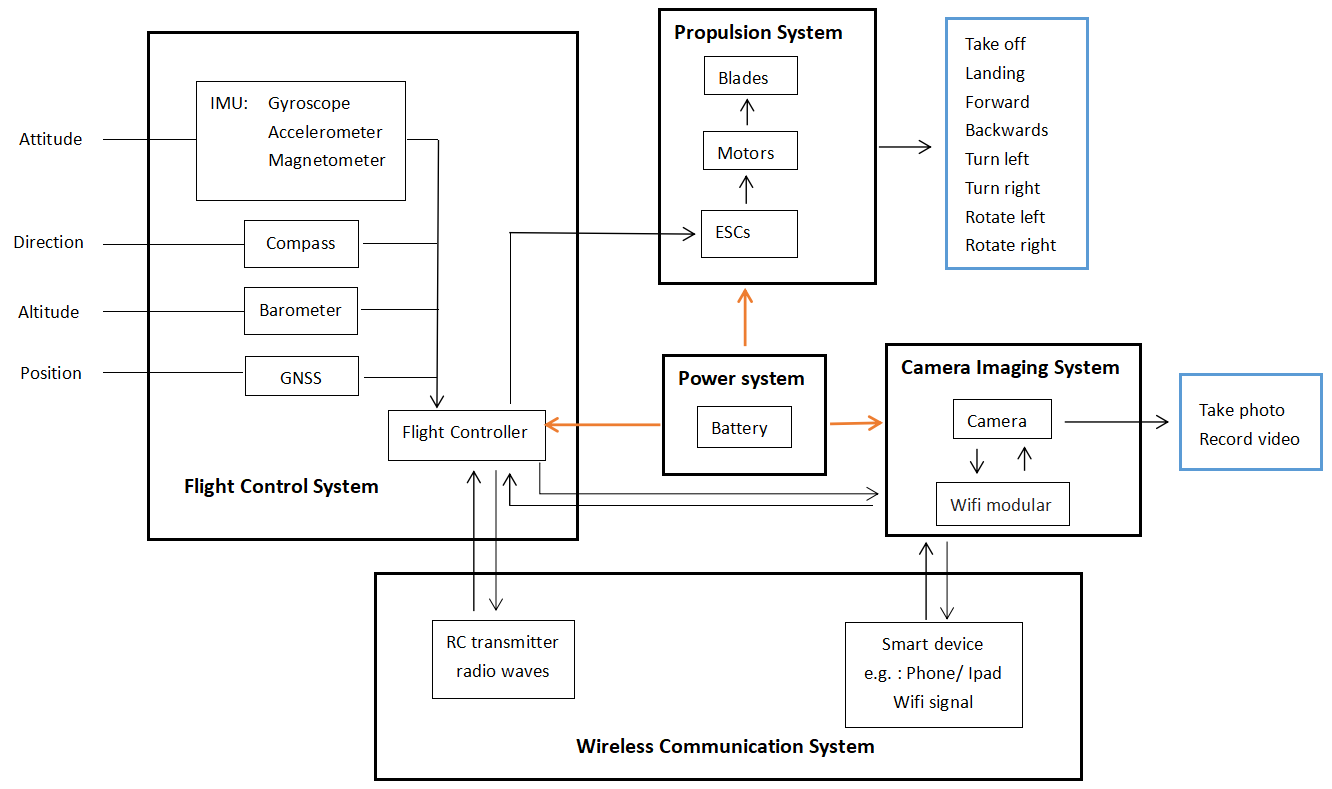

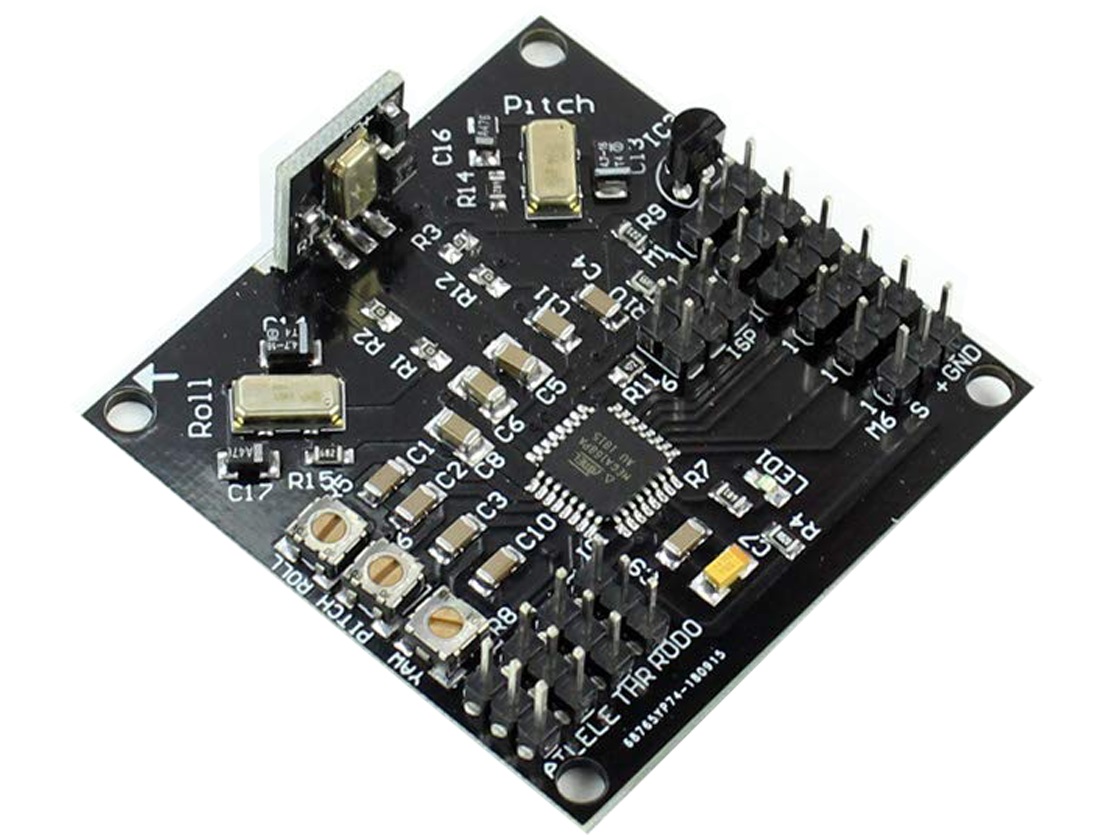

#FlightControlSystem

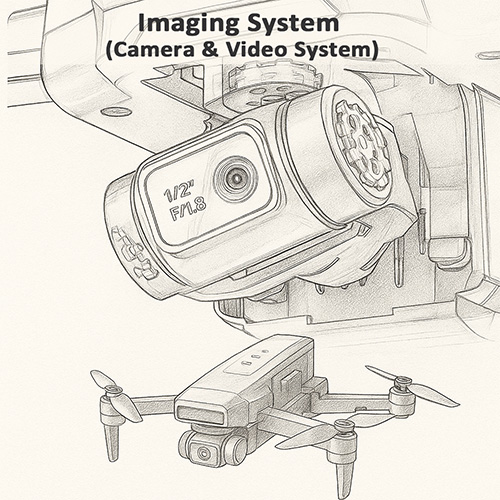

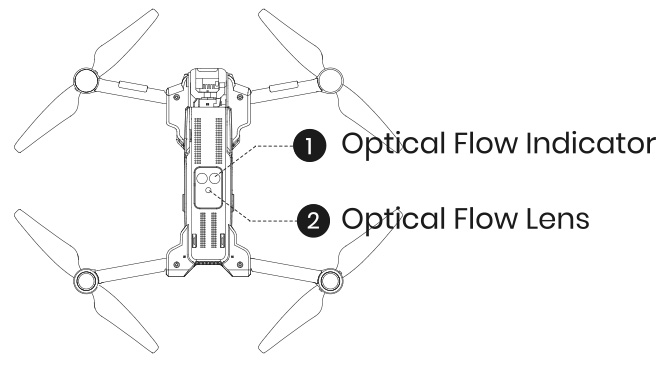

#FlightControlSystem #ImagingSystem

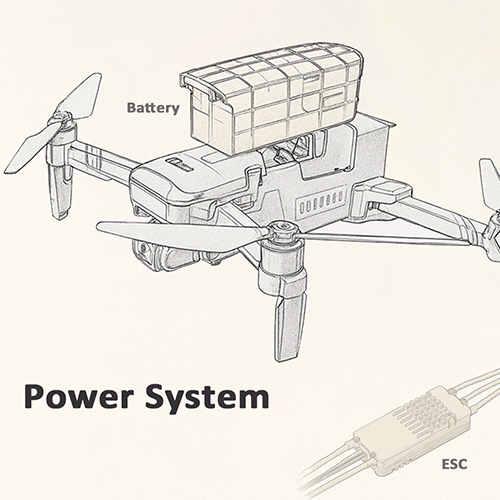

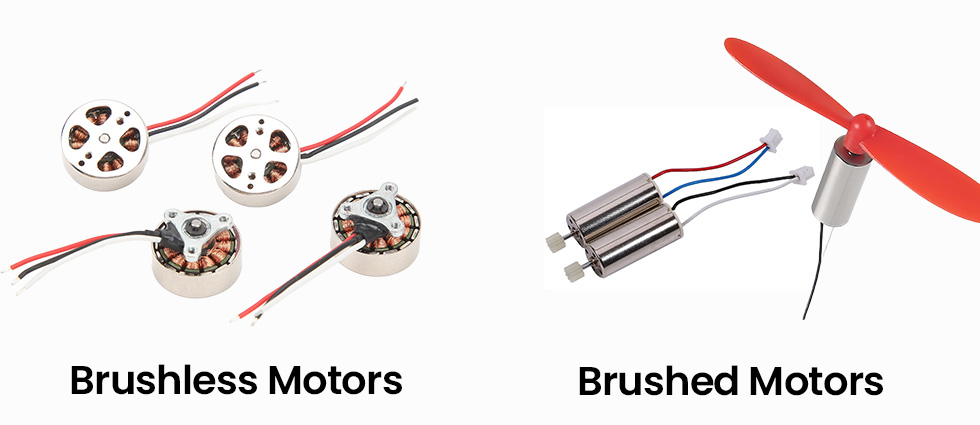

#ImagingSystem #PowerSystem

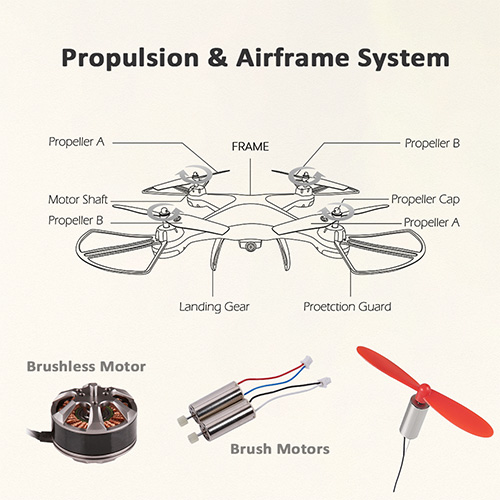

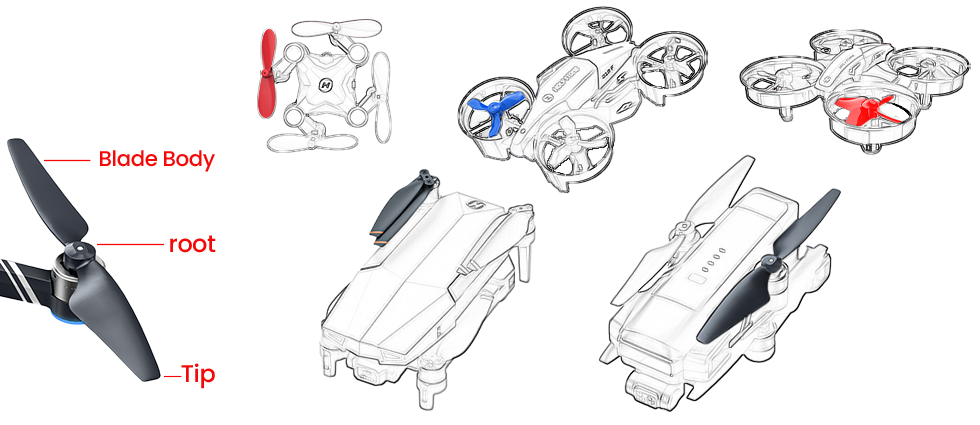

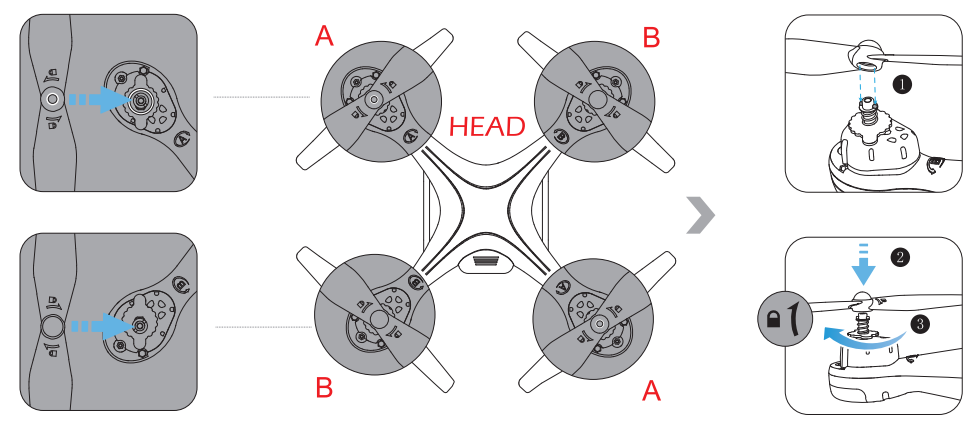

#PowerSystem #PropulsionSystem

#PropulsionSystem #WirelessCommunicationSystem

#WirelessCommunicationSystem

COMMENTS